This article was originally published on the Data Journalism Awards Medium Publication managed by the Global Editors Network. You can find the original version right here.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

After a year of hard work, collecting and sifting through hundreds of data projects from around the world, the news is finally out. The thirteen winners (and one honourable mention) of the Data Journalism Awards 2018 competition were announced on 31 May in Lisbon. Together they are the best of what the world of data journalism had to offer in the past year. They also teach us a lot about the state of data journalism.

All of the work I have done over the past few months has given me a pretty good perspective of what’s going on in the world of data journalism. Managing the Data Journalism Awards competition is probably the greatest way to find out what everybody has been up to and to discover amazing projects from all over the world.

And today I want to share some of this with you! Most of the examples you will see in this article are projects that either won or got shortlisted for the Data Journalism Awards 2018 competition.

When a news organisation submits a project, they have to fill in a form asking them to describe their work, but also how they made it, what technology they used, what methodology… And all of this information is published on the website for everyone to see.

So if you‘re reading this article in the hope of finding some inspiration for your next project, as I am confident you are, then here is a good tip: on top of all of the examples I will show you here, you can take a look at all of the 630 projects from all over the world which were submitted this year, right on the competition website. You’re welcome.

So what have we learned this year by going through hundreds of data journalism projects from around the world? What are the trends we’ve spotted?

Data journalism is still spreading internationally

And this is great news. We see more and more projects from countries that have never applied before, and this is a great indicator of the way journalists worldwide, regardless of their background, regardless of how accessible data is in their country, regardless of how data literate they are, are trying to tell stories with data.

Some topics are more popular than others

One of the first things we look at when we get the list of projects each year, is what topics did people tackle? And what we’ve learned from that is that some topics are more attractive than others.

Whether that’s because it is just easier to find data on them, or it’s easier to visualise things related to those topics, or it’s just the kind of big stories that everyone expects to see data on each year, we can’t really know for all of them. It’s probably a good mixture of all of this.

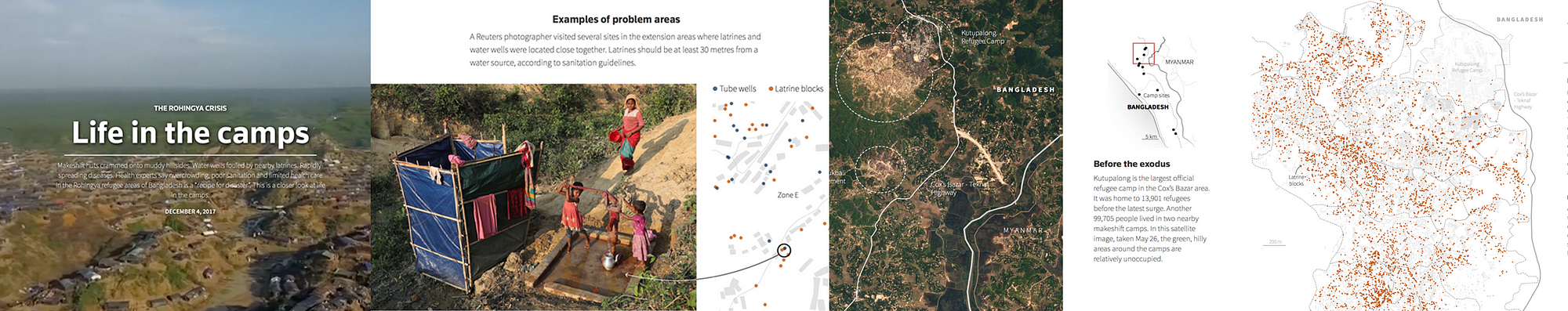

The refugee crises

The first recurrent topic that we’ve seen this past year is the refugee crises. And a great example of that is this project by Reuters called ‘Life in the camps’, which won the award for Data visualisation of the year at the Data Journalism Awards 2018.

This graphic provided the first detailed look at the dire living conditions inside the Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar. Using satellite imagery and data, the graphic documented the rapid expansion and lack of infrastructure in the largest camp cluster, Kutupalong. Makeshift toilets sit next to wells that are too shallow, contaminating water supply.

This project incorporates data-driven graphics, photo and video. Reuters gained access to data from a group of aid agencies working together to document the location of infrastructure throughout the Kutupalong camp by using handheld GPS devices on the ground. The graphics team recognised that parts of the data set could be used to analyse the accessibility of basic water and sanitation facilities. After some preliminary analysis, they were able to see that some areas had water pumps located too close to makeshift toilets, raising major health issues.

They displayed this information in a narrative graphic format with each water pump and temporary latrine marked by a dot and overlaid on a diagram of the camp footprint. They compared these locations to the U.N.’s basic guidelines to illustrate the potential health risks. Reuters photographers then used these coordinates to visit specific sites and document real examples of latrines and water pumps in close proximity to each other.

Technologies used for this project: HTML, CSS, Javascript, QGIS and Illustrator.

Elections/Politics

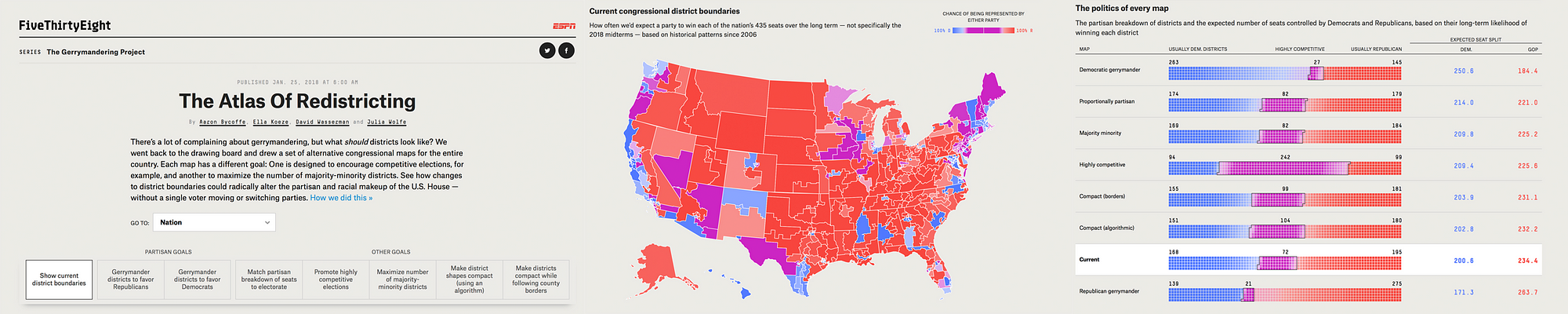

Next topic that came up a lot this year was politics, and more specifically, anything related to recent elections, not just in the US, but also in many other countries. One great example of that was the Data Journalism Awards 2018 ‘News data app of the year’ award winner, ‘The atlas of redistricting’, by FiveThirtyEight in the US.

There’s a lot of complaining about gerrymandering (the process of manipulating the boundaries of an electoral constituency so as to favour one party or class) and its effects on US politics. But a fundamental question is often missing from the conversation: What should political boundaries look like? There are a number of possible approaches to drawing districts, and each involves tradeoffs. For this project, the team at FiveThirtyEight looked at seven different redistricting schemes; and to quantify their tradeoffs and evaluate their political implications, they actually redrew every congressional district in the U.S. seven times. The Atlas of redistricting allows readers to explore each of these approaches — both for the nation as a whole and for their home state.

The scope of this project really makes it unique. No other news organization covering gerrymandering has taken on a project of this size before.

To make it happen, they took precinct-level presidential election results from 2012 and 2016 and reallocated them to 2010 Census voting districts. That enabled them to add more up-to-date political data to a free online redistricting tool called Dave’s Redistricting App. Once the data was in the app, they started the long process of drawing and redrawing all the districts in the country. Then, they downloaded their district boundaries from the app, analysed their political, racial and geometric characteristics, and ultimately evaluated the tradeoffs of the different redistricting approaches. Sources for data included Ryne Rohla/Decision Desk HQ, U.S. Census Bureau, and Brian Olson.

Technologies used for this project: Ruby, PostGIS, Dave’s Redistricting App, Node, D3

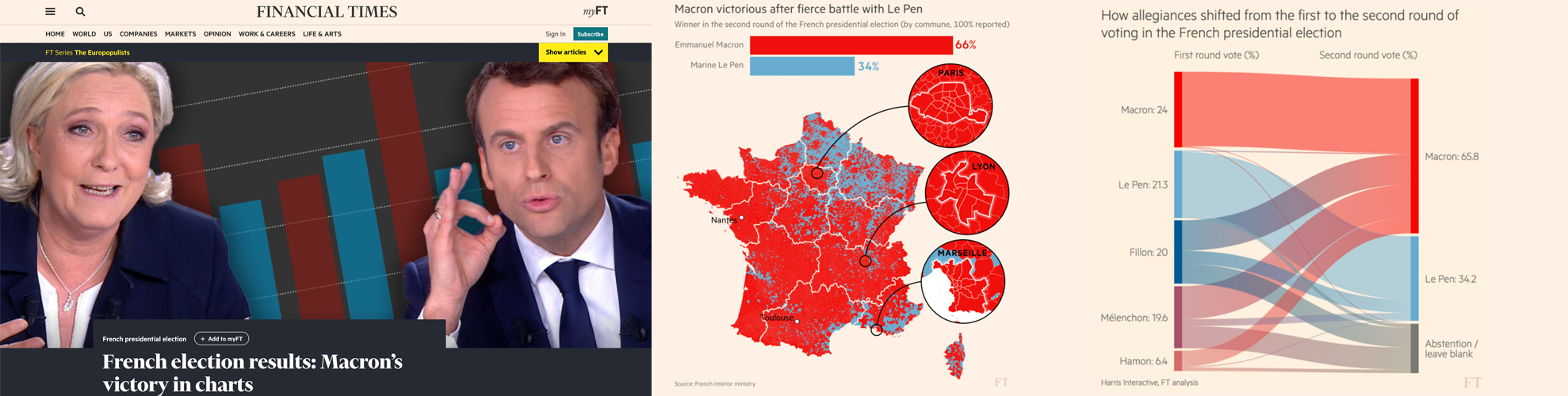

An other great example of how politics and elections were covered this year comes from the Financial Times. It is called ‘French election results: Macron’s victory in charts’ and was shortlisted for the Data Journalism Awards 2018 competition.

Let’s say it, elections are a must for all data news teams around the world. That’s probably the topic where the audience is the most used to seeing data combined with maps, graphics and analysis.

Throughout 2017 and 2018, the Financial Times became an expert in:

- producing rapid-response overnight analyses of elections,

- leveraging their data collection and visualisation skills to turn around insightful and visually striking reports on several elections across Europe,

- responding faster than other news organisations both in the UK and even those based in the countries where these elections have taken place.

Over and above simply providing the top-line results, they have focused on adding insight by identifying and explaining voting patterns, highlighting significant associations between the characteristics of people and places, and the political causes they support.

To deliver this, the team developed highly versatile skills in data scraping and cleaning. They also have carried out ‘election rehearsals’ — practice runs of election night to make sure their workflows for obtaining, cleaning and visualising data were all polished, and robust to avoid any glitches that might come up on the night of the count.

The work has demonstrably paid off, with readers from continental Europe outnumbering those from Britain and the United States — typically far larger audiences for the FT — for the data team’s analyses of the French, German and Italian elections.

For each election, the team identified official data sources at the most granular possible level, with the guidance of local academic experts and the FT’s network of correspondents.

R scripts were written in advance to scrape the electoral results services in real time and attach them to the static, pre-sourced demographic data.

Scraping and analysis was primarily conducted in R, with most final projection graphics created in D3 — often adapting the Financial Times’ Visual Vocabulary library of data visualisation formats.

Technologies used for this project: R, D3.

Crime

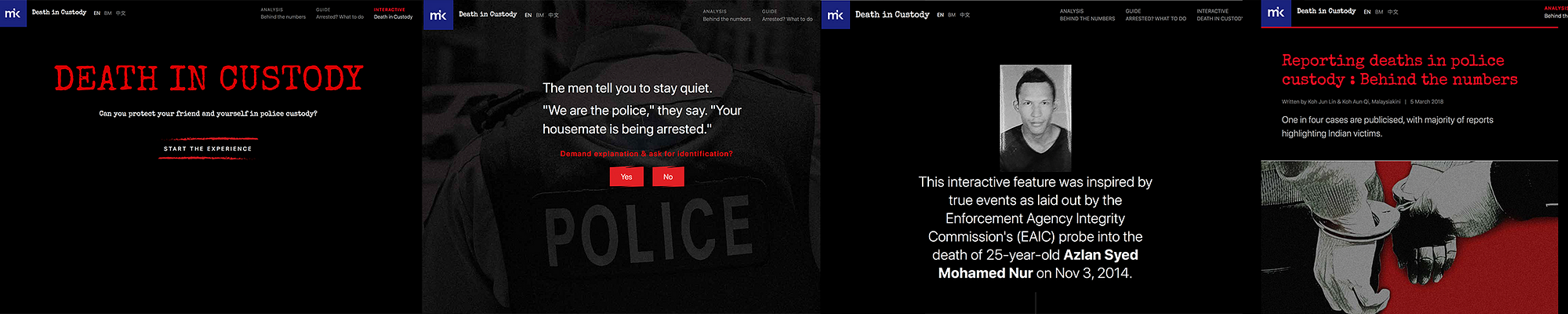

The last topic that I wanted to mention that was also recurrent this past year is crime. And to illustrate this, I’ve picked a project called ‘Deaths in custody’ by Malaysiakini in Malaysia.

This is an analysis of how deaths in police custody are reported, something that various teams around the world have been looking at recently. The team at Malaysiakini compared 15 years of official police statistics with data collected by a human rights organisation, called Suaram. The latter is the sole and most comprehensive tracker of publicised deaths in police custody in the country.

The journalists behind this project found that overall, deaths in Malaysian police custody are underreported, with one in four deaths being reported to the media or to Suaram.

They also highlight the important role that families of victims play in holding the police accountable and pushing to investigate the deaths. They created an interactive news game and a guide on what to do if somebody is arrested, both of which accompany the main article, taking inspiration from The Uber game that the Financial Times developed in 2017.

The game puts players in the shoes of a friend who is entangled in a custodial dilemma between a victim and the police. Along the way, there are fact boxes that teach players about their rights in custody. The real-life case that the game is based on is revealed at the end of the game.

Technologies used for this project: Tabula, OpenRefine, Google Sheets, HTML, CSS, Javascript, UI-Kit Framework, Adobe Photoshop.

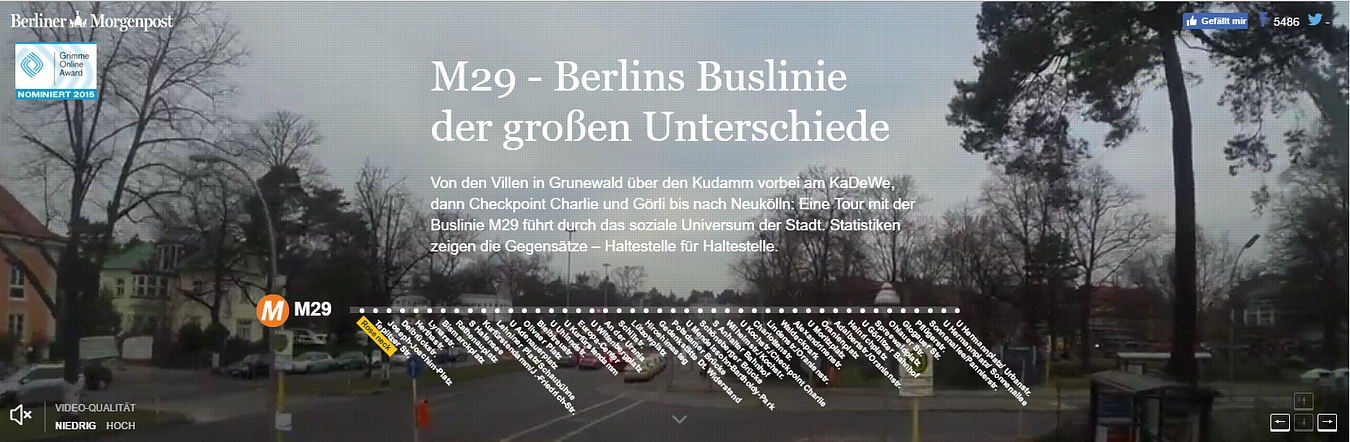

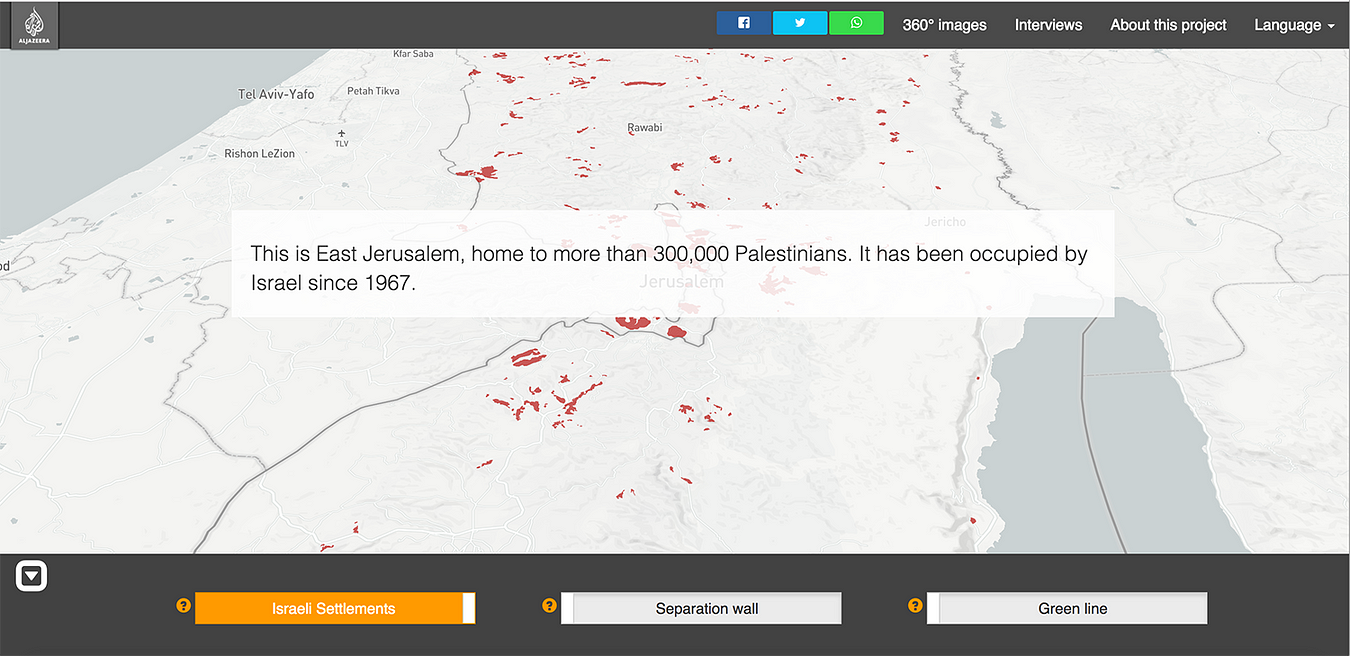

We’ve changed the way we do maps

Another thing that we’ve learned by looking at all these data journalism projects is that we have changed the way we do maps.

Some newsrooms are really getting better at it. Maps are more interactive, more granular, prettier too, and integrated as part of a narrative instead of standing on their own, making us think that more and more journalists don’t do maps for the sake of doing maps, but for good reasons.

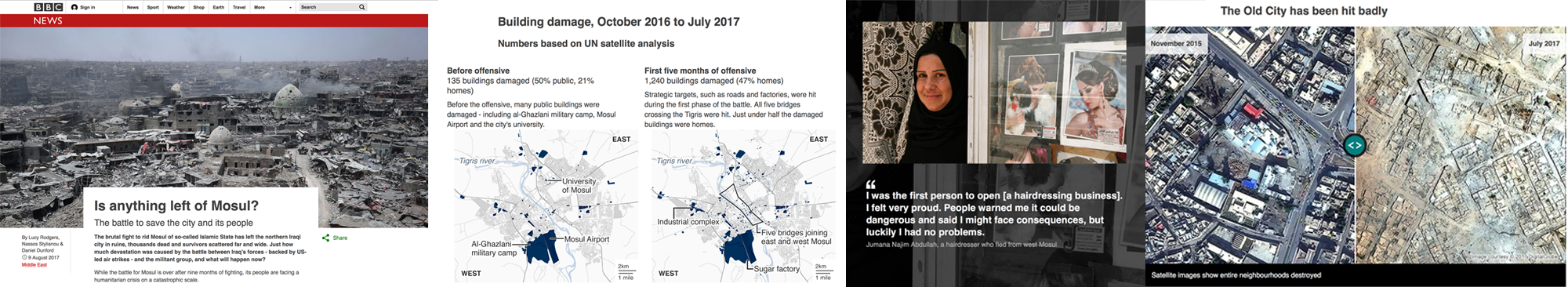

An example of how data journalists have made use of maps this past year is this piece by the BBC called ‘Is anything left of Mosul?’

It is a visually-led piece on the devastation caused to Mosul, Iraq, as a result of the battle to rid the city of Islamic State (IS). The piece not only gives people a full picture of the devastating scale of destruction, it also connects them to the real people who live in the city — essential when trying to tell stories from places people may not instantly relate to.

It was also designed mobile-first, giving users on small screens the full, in-depth experience. The feature uses the latest data from Unosat, allowing the BBC team to map in detail which buildings had suffered damage over time, telling the narrative of the war through four maps.

The feature incorporates interactive sliders to show the contrast of life before the conflict and after — a way of giving the audience an element of control over the storytelling.

They also used the latest data from the UNHCR, which told them where and when displaced people in Iraq had fled to and from. They mapped this data using QGIS’ heatmapping software and visualised it using their in-house Google Maps Chrome extension. They produced three heatmaps of Mosul at different phases of the battle, again telling a narrative of how the fighting had shifted to residential targets as the war went on.

The project got nearly half a million page views over several days in English. They also translated the feature into 10 other languages for BBC World Service audiences around the world.

Technologies used for this project: QGIS mapping software, Microsoft Excel, Adobe Illustrator, HTML, CSS, Javascript, Planet satellite imagery, DigitalGlobe images

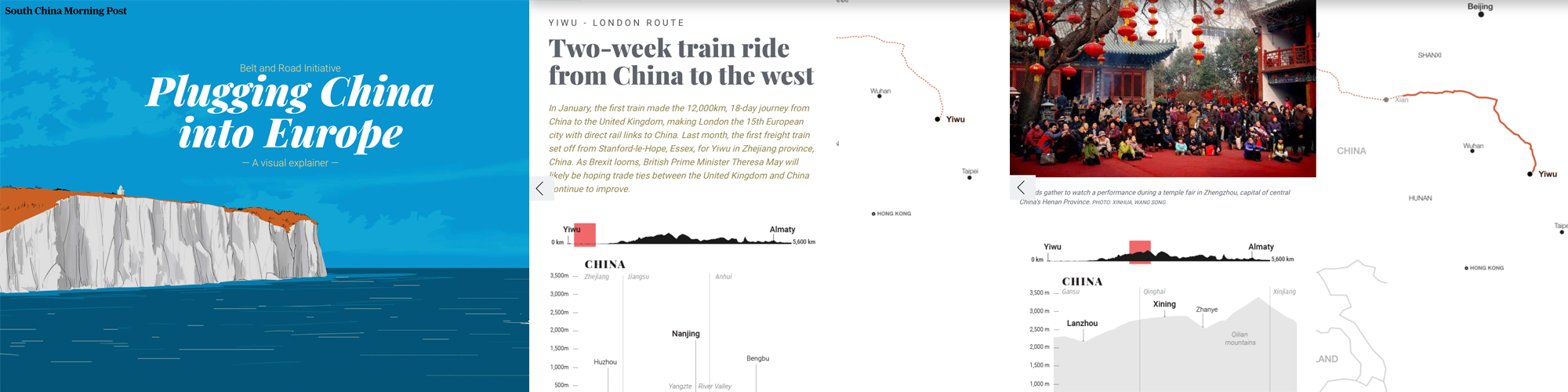

Another example of how the data journalism community has changed the way it does maps, is this interactive piece by the South China Morning Post called ‘China’s Belt and Road Initiative’.

The aim of this infographic is to provide context to the railway initiative linking China to the West.

They combined classic long-form storytelling with maps, graphs, diagrams of land elevations, infrastructure and risk-measurement charts, motion graphics, user interaction, and other media. The variety of techniques were selected to prevent the extensive data from appearing overwhelming. The split screen on the desktop version meant readers could refer to the route as they read the narrative.

We are not talking about boring static maps anymore. And this is an example of how new teams around the world, and not just in western countries, are aiming for more interactivity, and a better user journey through data stories, even when the topic is complex. It is thanks to the interactivity of the piece and the diversity of elements put together that the experience becomes enticing.

They used data from the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). Using Google Earth, they plotted and traced the path of each initiative to obtain height profiles and elevations to explain the extreme geographical environments and conditions.

Technologies used for this project: Adobe Creative Suite (Illustrator, Photoshop…), QGIS Brackets io Corel Painter, Microsoft Excel, Javascript, Canvas, JQuery, HTML, CSS — CSS3, Json, CSV, SVG.

New innovative data storytelling practices have arrived

Another thing we saw was that data teams around the world are finding new ways to tell stories. New innovative storytelling practices have arrived and are being used more and more.

Machine learning

It is probably the most used term in current conversations about news innovation. It has also been used recently to help create data-driven projects, such as ‘Hidden Spy Planes’ by BuzzFeed News in the US, the winner of the JSK Fellowships award for innovation in data journalism at this year’s Data Journalism Awards.

This project revealed the activities of aircrafts that their operators didn’t want to discuss, opening the lid on a black box of covert aerial surveillance by agencies of the US government, the military and its contractors, and local law enforcement agencies.

Some of these spy planes employed sophisticated surveillance technologies including devices to locate and track cell phones and satellite phones, or survey Wi-Fi networks.

Before these stories came out, most Americans would have been unaware of the extent and sophistication of these operations. Without employing machine learning to identify aircraft engaged in aerial surveillance, the activities of many of aircraft deploying these devices would have remained hidden.

In recent years, there has been much discussion about the potential of machine learning and artificial intelligence in journalism, largely centered on classifying and organising content with a CMS, on fact-checking for example.

There have been relatively few stories that have used machine learning as a core tool for reporting, which is why this project is an important landmark.

Technologies used for this project: R, RStudio, PostgreSQL, PostGIS, QGIS, PostGIS, OpenStreetMap

Drone journalism

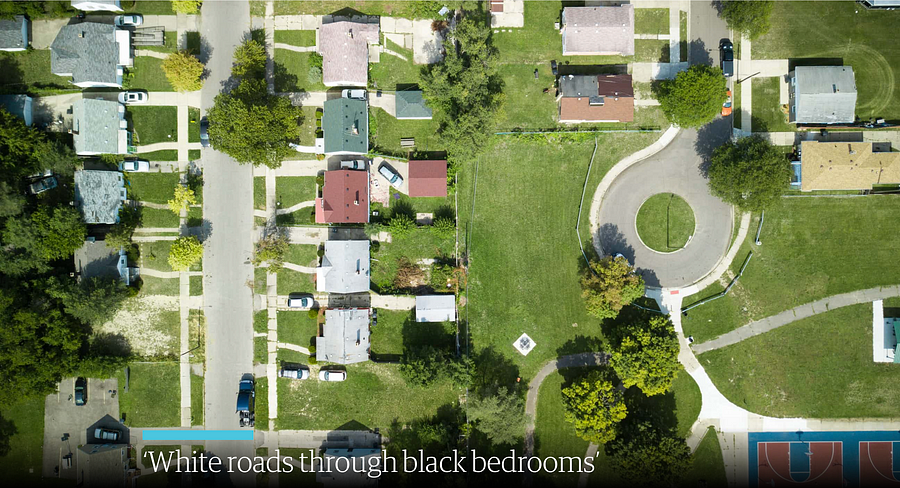

Another innovative storytelling practice that we’ve noticed is drone journalism, and here is an example called ‘Roads to nowhere’ from The Guardian.

It is an investigation using drone technology, historical research and analysis, interviews, as well as photomosaic visualizations.

It was a project that specifically looked at infrastructure in the US and the root causes of how cities have been designed with segregation and separation as a fundamental principle. It shows through a variety of means how Redlining and the interstate highway system were in part tools to disenfranchise African-Americans.

People are still living with this segregation to this day.

Most of the photos and all of the videos were taken by drone in this project. This is innovative in that it is really the only way to truly appreciate some of the micro-scale planning decisions taken in urban communities throughout the US.

Technologies used for this project: DJI Mavic Pro drone, a Canon 5Diii camera to take the photos, Shorthand, Adobe Photoshop. Knightlab’s Juxtapos tool to make it come to life with the slide tool

AR

Another innovative technique that has a lot of people talking at the moment is Augmented Reality, and to illustrate this in the context of data journalism, I am bringing you this project called ExtraPol by WeDoData in France.

Extrapol is an augmented reality app (iOS and Android) that was launched a month before the French presidential campaign in April 2017. Everyday, official candidates posters could be turned into new live data visualisations to inform the audience on the candidates. This data journalism project treated 30 topics in data such as: their geographical travels in France during the campaign, the cumulated number of years they have ruled a political mandate, etc.

This is probably the first ephemeral daily data journalism news app which uses augmented reality. This was the first time that real life materials, the official candidates posters, were ‘hacked’ to fact news on the politicians.

Technologies used for this project: Python, Javascript, HTML, CSS, PHP, jsFeat, TrackingWorker, Vuforia, GL Matrix, Open CV, Three.js, Adobe Illustrator, After Effect and Photoshop

Newsgames

They aren’t a new trend, but more and more newsrooms are playing with this. And this example, called ‘The Uber Game’ by the Financial Times in the UK, has been a key player in the field this year, inspiring news teams around the world…

This game puts you into the shoes of a full-time Uber driver. Based on real reporting, including dozens of interviews with Uber drivers in San Francisco, it aims to convey an emotional understanding of what it is like to try to make a living in the gig economy.

It is an innovative attempt to present data reporting in a new, interactive format. It was the third-most read by pageviews throughout 2017.

Roughly two-thirds of people who started the game finished it — even though this takes around 10 minutes and an average of 67 clicks.

Technologies used for this project: Ink to script the game, inkjs, anime.js, CSS, SCSS, NodeJS, Postgres database, Zeit Micro, Heroku 1X dynos, Standard-0 size Heroku Postgres database, Framer, Affinity Designer

Collaborations are still a big thing

And many organisations worldwide have had a go at it, in many regions around the world.

Paradise Papers

Of course we have the Paradise Papers investigation (pictured above) coordinated by the ICIJ with 380 journalists worldwide.

Based on a massive leak, it exposes secret tax machinations of some of the world’s most powerful people and corporations. The project revealed offshore interests and activities of more than 120 politicians and world leaders, including Queen Elizabeth II, and 13 advisers, major donors and members of U.S. President Donald J. Trump’s administration. It exposed the tax engineering of more than 100 multinational corporations, including Apple, Nike, Glencore and Allergan, and much more.

If you want to know more about how this was done, go to the Data Journalism Awards 2018 website where that information is published.

The leak, at 13.4 million records, was even bigger in terms of the number of records than the Panama Papers, and technically even more complex to manage.

The record set came from an array of sources from 19 secrecy jurisdictions. It also contained more than 110,000 files in database or spreadsheet formats (excel, CSVs and SQL). ICIJ’s data unit used reverse-engineering techniques to reconstruct corporate databases. The team scraped the records in the files and created a database with information of companies and individuals behind them.

The team then used ‘fuzzy matching’ techniques and other algorithms to compare the names of the people and companies in all these databases to lists of individuals and companies of interest, including prominent politicians and America’s 500 largest publicly traded corporations.

Technologies used for this project:

- For data extraction and analysis: Talend Open Studio for Big Data, SQL Server, PostgreSQL, Python (nltk, beautifulsoup, pandas, csvkit, fuzzywuzzy), Google Maps API, Open Street Maps API, Microsoft Excel, Tesseract, RapidMiner, Extract

- For the collaborative platforms: Linkurious, Neo4j, Apache Solr, Apache Tika, Blacklight, Xemx, Oxwall, MySQL and Semaphor.

- For the interactive products: JavaScript, Webpack, Node.js, D3.js, Vue.js, Leaflet.js and HTML.

- For security and sources protection: GPG, VeraCrypt, Tor, Tails, Google Authenticator, SSL (client certificates) and OpenVPN.

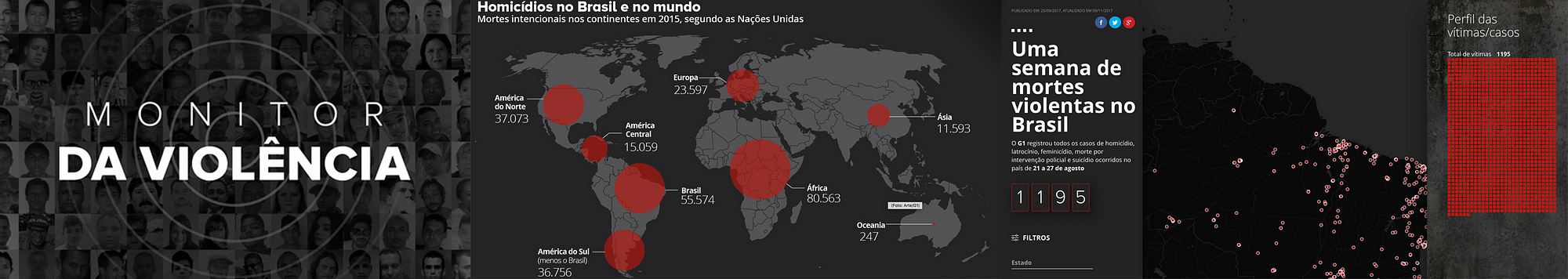

Monitor da violencia

Now here is an other collaborative project that you may not know of but is also quite impressive. It is called ‘Monitor da Violencia’, and it won the Microsoft award for public choice at this year’s Data Journalism Awards. It was done by G1 in Brazil, in collaboration with the Center for the Study of Violence at University of São Paulo (the largest university in Brazil) and the Brazilian Forum of Public Security (one of the most respected public security NGOs in Brazil).

This project is an unprecedented partnership which tackles violence in Brazil. To make it possible, G1 staff reporters all over Brazil kept track of violent deaths through the course of one week. Most of these are crimes that generally become forgotten — cases of homicides, robberies, deaths by police intervention, and suicides. There were 1,195 deaths in this period — one every 8 minutes on average.

All these stories have been cleared and written by more than 230 journalists spread throughout Brazil. This is a small sample — compared to the 60,000 annual homicide rate — but it represents a picture of the violence in Brazil.

The project aims at showing the faces of the victims; trying to understand the causes of this epidemic of deaths. As a first step, a news piece was written for each one of the violent deaths. An interactive map, complete with search filters, showed the locations of the crimes as well as the victim’s photos.

The second step was a collective and collaborative effort to find the names of unidentified people. A campaign was launched, including online, on TV and social media, so that people could help identify many of the victims.

A database was assembled from scratch, containing information such as the victims’ name, age, race, and gender. Also, the day, time, weapon used, and the exact location of the crime, among others.

Technologies used for this project: HTML, CSS, Javascript, Google Sheets, CARTO

Onwards and upwards for data journalism in 2018

The jury of the Data Journalism Awards, presided over by Paul Steiger, selected 13 winners (and one honorable mention) out of the 86 finalists for this year’s competition, and you can find the entire list, accompanied by comments from jury members, on the Data Journalism Awards website.

The insights I’ve listed in this article today show us that not only is the field ever-growing, it is also more impactful than ever, with many winning projects bringing change in their country.

Congratulations again to all of the winners, shortlisted projects, but also to all the journalists, news programmers, and NGOs pushing boundaries so that hard-to-reach data becomes engaging and impactful projects for news audiences.

The competition, organised by the Global Editors Network, with support from the Google News Initiative, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Microsoft, and in partnership with Chartbeat, received 630 submissions of the highest standards from 58 countries.

Now in its seventh year, the Data Journalism Awards was launched in 2012. In the first edition, it received close to 200 projects. Over the years it has grown to become the first international awards recognising outstanding work in the field of data journalism, receiving the highest amount of submissions in the history of the competition in 2018.

Marianne Bouchart is the founder and director of HEI-DA, a nonprofit organisation promoting news innovation, the future of data journalism and open data. She runs data journalism programmes in various regions around the world as well as HEI-DA’s Sensor Journalism Toolkit project and manages the Data Journalism Awards competition.

Before launching HEI-DA, Marianne spent 10 years in London where she worked as a web producer, data journalism and graphics editor for Bloomberg News, amongst others. She created the Data Journalism Blog in 2011 and gives lectures at journalism schools, in the UK and in France.